Afropop

Introduction

For two decades, the African continent has been living to the beat of successive types of choreographic and musical fever, both digital and urban, that have crossed borders to “infect” the youth in more distant regions. They are known as Kwaito, Pantsula, Ndombolo, Mapouka, Coupé Decalé, Kuduro, Pinguiss, Afrobeats, and Azonto. Despite their varied origins, expressed in their colourful forms, they still have a certain number of characteristics in common. First of all, they do not separate dance and music; a musical creation cannot exist without its choreographic other half, and vice versa. Then, using body language, the choreographies creates links where the uninitiated eye only sees paradoxes: these styles reunite traditional heritage with the modernity of everyday life; they superimpose the local and the global; they simultaneously express the realities of the have-nots and their dreams of gold. Finally they create new cultural flows between people living on the continent and their communities scattered throughout the world, which have become an essential relay for the creation and exchange of these artistic works. A multitude of different features that, according to their followers, go to make up the essence of a contemporary continental genre known as Afropop.

Africa "On The Beat"

Afropop is the celebration of a modern Africa, in phase with a globalization that is changing spatial, social, and cultural barriers.

In the discourse of young African artists, we find the image of a united Africa, one without any borders, one where local and national practices and heritage are mixed with influences and imagery from other regions. A style invented in one country is adopted a few months later by a different one thousands of kilometres away, eventually to become the proud expression of the whole of the continent. The Coupé Décalé, an Ivory Coast-style choreographic and musical genre incorporates many steps and dances from the Soukous and the Congolese Ndolombo. It was created in France, but developed in Ivory Coast, and quickly spread throughout French-speaking Africa. These dances are not only intended for a local and national audience; its creators are now looking to reach an international audience. Musicians and choreographers are trying to win over the world through the use of a global language: three-minute videos broadcast on the Internet using a common languages (French, English, etc.) to explain these new dances and encourage viewers to copy them at home or in public areas, to disseminate their latest choreographic creations as best they can.

"This Is New Africa" says Fuse ODG, one of the emblematic representatives of this Afropop generation. Far from the clichés of a poverty-stricken continent that are too often projected in the West, this young generation presents a winning Africa, in tune with capitalist globalization. Dancers proudly show off their designer clothes, branded watches, jewellery, gleaming cars, and the latest technologies. This is a radiant Africa and it wants the rest of the world to know it. These dances show a liberated, individualistic youth, which is flourishing in a world of pure entertainment. They show off their bodies, they play at having sex. The contemporary versions of the Senegalese Sabbar or the Ivory Coast Mapouka have a lot in common with the latest videos of Jamaican Dancehall and the American Twerk on the other side of the Atlantic.

Africa "Off the Beat"

Behind this portrait of an over-the-top, showy continent, a more complex reality is being seen and heard by initiates, where messages, heritage and expressions of identity are transmitted unnoticeably.

Pinguiss mania

Report made in Douala in Cameroon, Paris and Sarcelles focusing on the phenomenon of the Pinguiss dance, which is electrifying Cameroonian clubs.

Commentary on real images and extracts from a clip alternated with an interview with Daniel, the Cameroonian inventor of this dance, and dancers...

It was Daniel Baka'a who invented the Pinguiss, a dance that is as unusual as it is energetic. Energetic because the 'Pinguiss' is practically danced on one leg.

The dancer must hop on one leg, spin around and go in all directions: forwards,

backwards, sidewards, and so on...

The Africa presented to us in Afropop music videos is in strong contrast with the actual daily lives of the people who dance it. They are often deprived of the nation’s wealth and limited in their possibilities to travel or emigrate to other countries. The fragmented African continent struggles to reunite itself. African countries are suffering from repeated political and economic crises, and even when this is not the case, there is often war, epidemics or starvation. Through dance, by incarnating their hopes, their dreams, their fantasies, they can, at least for a short while, attain what they do not possess and what they are prohibited from having: the unemployed can work, those without documents can travel, the poor can be rich... The occasional use of coded polysemous language, be it verbal, choreographic, iconographic or musical, allows for new horizons to be opened up to this African generation, and allows them to define a personalisable area of freedom in between the lines of an existence that knows nothing but constraints.

But the eyes of this young generation not only look to a hypothetical future, they go beyond a fantasized daily life, and their imaginary world. In-between the beats and the dance steps, you can also read a need to exist in the present reality with its firmly rooted heritage. If we look behind the appearance and the modernist discourse of Afropop we see in its expressions a local choreographic and musical heritage. The Azonto, a new Ghanaian dance performed in some London clubs is based on the Kpanlogo, which was danced during the sixties in Accra, itself based on the immemorial choreographic heritage of Ga society

These movements therefore have a daily social utility (be it conscientious and explicit or not) in the different worlds where their creators live: through body language they can speak about the unspeakable, criticize an arbitrary power, provide work for the idling populations, liberate shackled populations, or give a reason for living to marginalized populations...

Apartheid, the narrative of the body

The dance group is helping to ensure that the culture of the pantsula dance continues to live on. In many respects, the dance resembles American hip-hop and emerged in s similar way, in the 1980s. It originated in the street, it has its own language, music and dress codes. Pantsula dancing was banned during the Apartheid. This however just increased its popularity in the townships.

The dreams and protests that can be read between the lines in the different folk dances show what Africa’s youth is really thinking. When an individual seeks to define himself in a globalized world, in plurinational countries with disputed borders, in an urban environment that has forgotten its traditions and where he is confronted with a host of other people, dance is a natural tool that he can use to define his identity. Through Afropop, a new generation of artists can use their bodies to express who they are, where they come from, where they are going, whose ideas they share, and whose ideas they reject... This helps them to create an identity, to know where they belong. The resulting associations that they create are multiple, mobile, and specific to particular contexts. They can be family, religious, national, regional, linguistic and racial... Thus, by choosing to dance the Azonto rather than the Kuduro, two movements that generally fall under the category Afropop, they can show that they identify with a certain group rather than another. Dancing has therefore become a mainspring of identity, enabling them to build relationships, and to reunite individuals or groups of like-minded individuals around the same artistic activity. In 2001, at a time when Ivory Coast was experiencing an economic, political and military crisis that was threatening to turn into civil war, the Coupé Decalé and its different dances brought together a divided population under the same beat. A few years later, the whole of French-speaking Africa was gripped by the charm of this movement sung in French, while the African-French struggled to gain recognition in France.

Disasporic Africa: A choreographic mainspring

Afropop is not limited to the borders of the African continent. Through its migration, it has forged a global cultural network that communicates across the oceans around a common choreographic and musical activity.

The dances that fall under the category Afropop are part of a long history of black culture. For several centuries, cultural exchanges developed against a backdrop of triangular trade between descendants of Africa and Africans. These new emerging dances were dances of migrants shared by several generations of displaced populations. While the origins of the Kwaito were directly based on the sounds of North American House played more slowly, today the stars of American black pop music are adopting choreographic motifs that are to be found in Afropop. These current popular music types are fueled by the most recent African migration. After World War II, the different waves of migration to western countries, and in particular the former colonial countries, helped immigrant communities to form, and these communities are often the birthplace of such new dances and types of African pop music.

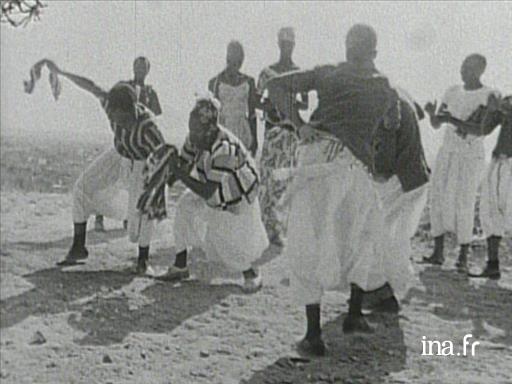

Africa in France 1967

Extract of a documentary dealing with the situation of immigrants from Senegal, Mali and Mauritania who came to work in Paris. To escape their harsh living conditions, in their homes located in the suburbs to the east of the capital, they get together, talk about their experiences, and try, as they say "to forget about their hardships through dance".

Dance was essential for these immigrant communities in exile, be they of Congolese, Ghanaian, Senegalese or Ethiopian origin.

Firstly, it was a means of communication that enabled them to exchange with their country of origin. The latest dance in fashion is an opportunity for diasporas to communicate with each other on a common subject. Thanks to digital technologies, the African youth around the world can film and share their performances, no matter the dance: Azonto, Coupé Decalé or Kuduro.

The choreographic medium (i.e. dance) also allows migrants to interact with the culture of their new country. The migrant can use it to create a unifying force (be it based on national identity - Mali, Cape Verde, regional or linguistic - French or Portuguese, religious...), and protect himself from the difficulties associated with his migratory experience (exclusion, isolation, oppression, poverty, and racism, etc.). The migrant may also choose to use the choreographic medium as a means of opening up, and interacting with other migrant communities or the indigenous people. These different choreographic exchanges between the two worlds help change people’s perception of migration (portraying an idealization of migration for those who stayed in the homeland, and disillusionment for migrants who dream of returning home), and new forms of expressions enriched through these encounters.

Another suburb, another time

Story about the Dervallieres district in Nantes. In Nantes, more than 25 nationalities rub shoulders every day. Like so many others, Guapo, Mariama and Mama are the offspring of immigrants. Perfectly integrated in the district, they retain the values and traditions of their African community. Guapo, Mariama and Mama have known each other since infant school. Their friendship is above all a story about land and maternal roots. They have got to know the district, they have their own routines. Together they created "Black Diamond", an African dance group. Tossed about between two completely different worlds, these three grinning girls have found their place in society and their own identity. Proud to be French, and also proud of their little piece of Africa.

The associations, exchanges, cultural assimilation, or rejection created by these forms of diasporic expression on contact with other countries are indicative of the development of new cultural flows.

In the 20th century, while we observe an unbalanced binary relationship between a (geographic, social, political, or aesthetic) central core that is attractive and radiant, and its passive and receiving outer layers, Afropop bears witness to more active outer layers, which exchange between themselves, affecting the central core. This development, which is only perhaps short-lived, sees central cores that invite their outer layers to the heart of the creative process: Azonto exists thanks to the link between Ghanaian minorities scattered throughout the suburbs of major western capitals; the Ivory Coast Coupé Décalé provided a stage for small gangsters who had emigrated to Paris; Nigerian Afrobeat artists inspire and lead productions with major African-American artists; Angolan Kuduro inspired the Lisbon electronic music scene, which then gained popularity throughout Europe.

When young Afro-descendants of Paris London, and New York dance in step with the youth of Cape Town, Lagos, or Abidjan, they are dancing to the anthem of a continent, called Afropop. Afropop: expression of the times rather than a formal style, is 21st century Africa soon to be a major player?