Capoeira, from one world to another

Introduction

In the 19th century, any Frenchman who had shown a keen interest in Brazil would have remembered capoeira, commonly referred to as the “game of warriors”, the “dance of Negroes”, or the “gymnastics for riff-raff”. During the first half of the next century, it is no longer talked about in France. At the time, Brazil’s wealth was associated with coffee, which was destroyed by the crisis of 1929 when people, unable to sell coffee grains, started to burn them as a fuel for locomotives.

In the 1930s, in Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia, the municipal authorities decided to promote tourism and make an inventory of all the important sights and attractions. The old town is picturesque, but the churches were sometimes falling into disrepair or surrounded by slums; there were no really famous architectural works of art. But there were the people: Bahia, close to Africa, is colorful and noisy. The people carried everything on their heads, they had their typical cuisine, their religions and their games. Passengers of cruise ships who had a stopover in Brazil were offered fine food & drink and dance performances: the sacred candomblé, the profane samba and capoeira. Among these people, who were strangers to hunger, were skilled people who were eager to earn more in one hour than they could get in a whole day doing much harder work. As a result, the police repression of candomblé and capoeira got lost in red tape.

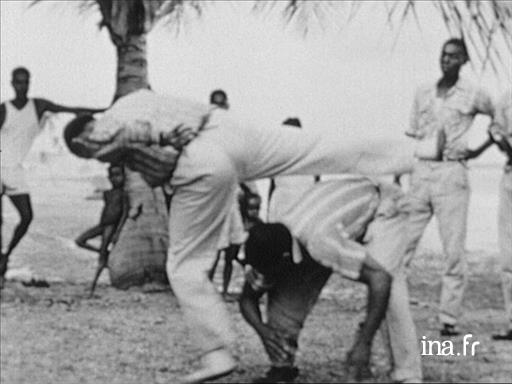

Bahia, capoeira on the beach

On a beach in Bahia, a group of dancers perform the steps of a capoeira, traditional dance, considered a martial art. Of African origin, (specifically Angolan), the capoeira is one of the cultural foundations of a mixed-race Brazil. A musical group accompanies the protagonists. The main instrument used is the berimbau.

Return to the tradition

Outside of trading circles and the municipal administration, the regional sentiment of Bahia was to make the offspring of the well-to-do study the region’s folklore and popular ethnography. They did not hesitate to visit the place where candomblé and capoeira were practised. In around 1950, we visit one of such areas, which was subsequently called Liberdade, and we see capoeira being performed in the hut built by Waldemar, one of the famous capoeirists of the time. French ethnologists Pierre Verger, Alfred Métraux, Simone Dreyfus attend the game. Tourists had to pay to see the performances and dances, which ended up being an important source of income for the state. Some organizers turned them into real shows, quite different from what was commonly thought as folklore. The Journalist Vasconcelos Maia was concerned that the artificialization of customs might cause the tourist interest to dry up. As head of the Municipal Secretariat for Tourism, he worked hard to train tourist guides to be more knowledgeable in the history of the city and its customs, and promoted a more traditional approach to the practising of capoeira, which was probably best represented by the old master Pastinha. The others did what they wanted and considered capoeira either to be a martial art governed by the sound of the berimbau, as master Bimba did, or as an ordinary form of entertainment, which didn’t need to bend to any rules.

In 1962, the film Pagador de promessas (the Keeper of Promises) by Anselmo Duarte, in which capoeirists, dancers and troublemakers despite only playing a secondary role are nevertheless clearly present, won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It was perhaps this success that encouraged a television crew, equipped with two synchronous-sound cameras in 1963 to film Master Pastinha’s group, now dressed in uniforms, for a demonstration of capoeira; the commentary does not do too much injustice to the words in Portuguese.

The groups compete with each other to impress the journalists and in doing so produce diverging moves and rhythmic patterns. Many histories are also told as to the origins of capoeira, seemingly with all the freedom in the world as there is no documentation on capoeira before the end of the 18th century, and very little until the 20th. For friends of folklorists, like master Pastinha, capoeira is a “survival” of African culture. The duty of every capoeirist is to attempt to restore it to its origins, or in its purity. For others, like master Bimba, capoeira was a creation of blacks living in Brazil, whose intelligence and inventive capacity was not broken by slavery. Capoeira is an art that requires cunning and the ability to adapt to circumstances, qualities that are always essential, even in modern times. Slavery may have gone, but the chains of poverty still weigh heavily on blacks and those of mixed-origin, who make up the majority of the population of Bahia.

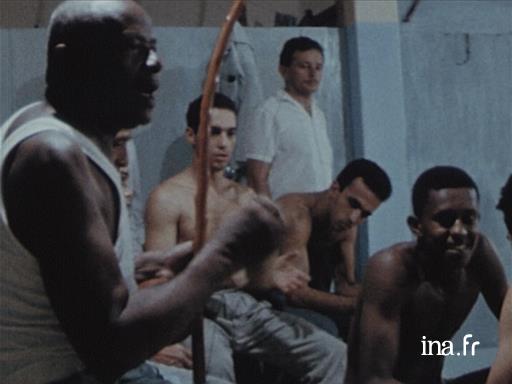

Capoeira: Master Bimba in Salvador de Bahia

In Bahia, young people follow the classes of master Bimba on how to perform capoeira, a martial art-like traditional dance of African origin, particularly Angola. The figures and moves are performed to the sound of a traditional musical instrument, the berimbau.

Capoeira, the show must go on

The military coup of 1964 saw the expulsion of Vasconcelos Maia. Traditionalist capoeira was in decline. Capoeira performances become increasingly more spectacular, employing acrobats and moves that could be seen from afar, and giving free reign to popular taste to add colour and spice. Master Bimba's Academy, and those of a few others like Carlos Senna, trained dozens of young people from the middle classes in the fighting side of capoeira; a few, like Bira Almeida a.k.a. Acordeon, also included the cultural dimension of capoeira. When Pierre Kast visited Brazil in 1968, he filmed a roda at the end of a class in Bimba.

For the French, capoeira continued to be one of Bahia’s exotic specialties. Yet, during the same years, the Bahian variant of capoeira spread throughout Brazil. Rio de Janeiro has had Bahians living there since the 19th century, but the game did not follow the same development in terms of folklore. It was regarded as a way to fight used by gangs, and the term capoeira, if not placed in a specific context, meant lout. This "special sort of gymnastics" was even more repressed here than in Bahia. But the economic boom, known as the Brazilian miracle, attracted inhabitants from the impoverished northeastern States of Brazil to the industrial cities of Rio and São Paulo, and consequently capoeira groups were also established in these large urban cities. In the early 1970s, the authoritarian and nationalist government supported the formation of capoeira federations, granting them a form of recognition that would allow them to evade police harassment. Within this legal framework, the academies grew and developed. The white uniform was introduced across the board, capoeira was practiced to the sound of the berimbau and pandeiro to which was rapidly added the atabaque drum and the agogo double Bell, which had formerly only been reserved for Afro-Brazilian worship. The style of play also evolved in a way that promoted physical stamina and the ability to read the opponents moves, rather than the ability to deceive underhandedly and conceal one intentions, as found in in the older version of the game.

Capoeira

In Paris, a capoeira dance class (battle-game-dance) with Brazilian music. Interview with Garcia Gómez de Suza on the origins of capoeira (a type of street fighting that Brazilian slaves, who did not have the right to fight, disguised as a dance form). Interview with Claudio Lemos, teacher, on what makes a good capoeira.

Imported to Europe

Academies of capoeira in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, where even the poorest students still had more money than those in Bahia, spread to Europe along with capoeira from the 1980s. Teaching dance attracted a public that had the means to pay, and the income it generated was often supplemented by earning from shows, which were quite often the main activity. The teachers were young adventurous people who made up for their lack of teacher training and knowledge of the tradition with their boldness and audaciousness. The issue of masters trained on the plane on their way to Europe was rocking capoeira circles, and older capoeirists decided to organise visits.

At the same time, a capoeirista, originally from Bahia, and solder in Rio de Janeiro, master Moraes, was critical of how capoeira was developing and founded a group (the GCAP) dedicated to re-africanizing the game, based on the model of what had happened to Afro-Brazilian religion at the beginning of the century. He took it on himself to reform the moves, the aesthetic and the format, initially imposing heavy restrictions designed to facilitate the reintroduction of those elements he wanted to see restored. After leaving the army and returning to Salvador, he succeeded with his group, despite its divisions, to profoundly transform capoeira, making old masters come out of retirement to ensure continuity and Afro-Brazilian authenticity. While the federation’s capoeirists dreamed of having capoeira accepted as an Olympic discipline, the GCAP enhanced the Black elements of Brazilian culture. Capoeira groups are generally organised around the personality of a master and divided by rivalries. They had to know- whether they wanted to do or not - position themselves vis-à-vis this opposition who was responsible for choosing the new members, who reinvented the legend of capoeira to their liking (as there is very little documentation relating to the history of capoeira and it is based mainly on legend), and who controlled the direction of training.

Brazil: Resistance in the Forte de Santo Antonio

In Bahía, associations including the GCAP looked after poverty-stricken children by encouraging them to engage in traditional dances, including capoeira. This dance, which is of Africa origin, chiefly Angola, often compared to a martial art. It was created by slaves who practised it to the sound of an instrument of Bantu origin, the berimbau. The film gives us a peek behind the doors of a school run by master Moraes, where children practise making the different figures of capoeira and then takes us to visit a musician and maker of berimbaus.

In Europe, in America, and Brazil, the dance side of capoeira did not fail to attract dancers and choreographers. The hip hop movement has certainly adopted some of its moves, and shares the same idea of dance and fight in its bad boy battles. We clearly see figures from capoeira that have been stylized in contemporary dance. In Salvador, the Bale Folclorico da Bahia fostered the link with popular culture, which was exuberant, exhibitionist, colourful and unbridled.

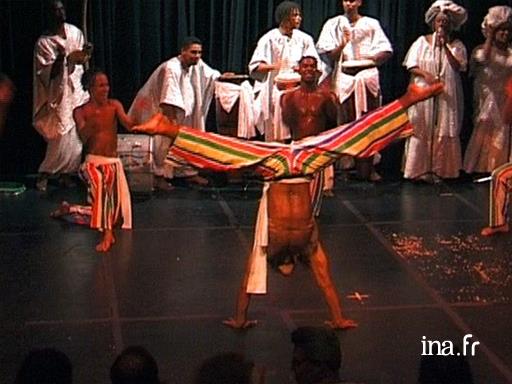

Lyon, one city’s two-step and a troupe from Salvador de Bahia

Arrival of the troupe at the biennale de danse in Lyon where they saw a performance of ballet from Bahia: The Bale Folclorico da Bahia. This troupe stages a capoeira dance show, a dance that is similar to a martial art. A dance of African origin, similar to a martial art, brought to Brazil by slaves. The film follows them in their town, Salvador de Bahia.

The term "capoeira angola"

It is likely that the terms “capoeira and “angola” are both false friends, i.e. unrelated to hen houses ("capoeira" in European Portuguese), nor to a clearing in the forest ("caa-poera" in Tupi, the native language of Brazil). Etymologists have come up with amazing explanations for them. The term “angola” may well have nothing to do with the C16 Kingdom of Angola (territory now located in the Congo) nor with the Portuguese Angola colony. According to Gerhard Kubik, and then by Guilhermo dos Santos, the most likely etymology for "Capoeira angola" is an expression in the Bantu Language (not especially an Angolan language: "kapwila ngolo", which literally meaning “beat one’s hands”, and by metonymy "amusement" for the first term, and “friends” for the second. These two terms were translated together by the "capoeira angola" movement to devise the Portuguese expression "vadiacao entre amigos”.

The origins of capoeira

Edison Carneiro believes that the game of capoeira (from Bahia) is a Bantu game, noting that comparable forms of stylistic fighting exist elsewhere in Brazil (albeit without the typical musical accompaniment), while Sahelians are especially numerous in Bahia, and while capoeirists and the people of candomblé were notoriously hostile to each other at the beginning of the 20th century. Carneiro believes that this hostility was due to a persistent cultural difference between Bantus and Sahelians.

In archival research conducted since, the national crime statistics for capoeira (whatever this expression may mean for the police) shows a predominance of Bantu in Rio de Janeiro in the early 19th century, which would support the hypothesis that it is indeed of Black origin. This predominance then slowly declined to the benefit of all nations. After the Paraguay war, the term capoeira in Rio seemed to be used in police reports, newspapers, parliamentary debates, as an equivalent to gangs (like those in North America today). Ethnic origins were even more varied, including European immigrants.

In Bahia, there is very little documentation on capoeira before Edison Carneiro. The police did not use the term capoeira in their reports (they talked about the carrying of firearms, riots, etc.). No document has ever been published associating the term desordeiros with a specific ethnic origin.

The berimbau, the musical bow used in the capoeira, which has a religious purpose in worshiping practices of Bantu origin in Brazil and Cuba, is another argument for placing the cultural origins of capoeira among the Bantu slaves in Brazil. Musical bows are prevalent in South Africa, but none are identical to that of Bahia, organologically speaking. However, they are rare in the Sahelian region. It is only in Bahia that it is used to accompany a dance, a fight or a game; everywhere else, the drum is used.

In Brazil, it is a good idea to have padrinhos, i.e godfathers with status. The capoeirists happily adopted the opinions of their godfathers as to the origins of the game, and thus they were free to do what they wanted. This was the reason why most of them defended the national idea up until 1950: Whites and blacks were all Brazilians on their way to becoming equal, and the most appropriate history for capoeira’s origins was the idea that capoeira was born in Brazil. The folklorist idea of the survival was favoured by the intellectual bourgeoisie of Bahia (Jorge Amado & Wilson Lins) and represented the influence of the mission of the Herskovits, who was the leading North American theorist to defend this explanation. He was sent to Brazil by the US Government in 1941, alongside several others, all of whom were a source of fascination for the Bahian people because of the academic authority with which they spoke and the amount of money they possessed. In Brazil, they were performed by the classical folklorist Câmara Cascudo.

Thanks to improved educational standards from the 1930s, the current capoeirists are now able to invent new stories as to their origins, and enjoy doing just that. We have drawn on journalistic publications, we have turned hypotheses made by researchers into facts, we have associates capoeira with all the main events in Brazilian history: the wars led by Palmares against a nation of tens of thousands of Black Maroons (1630 – 1698), the defence of the Maroon communities (quilombos), the legend of Chico Rei, (1740), political independence (1822-1823), the uprising of 1828 etc. We have used details (unknown to ethnologists) to present the dance that became the game of capoeira. These delightful stories give us vital insight into the state of mind of those who tell them.