Haka through the ages: from the founding myth to the rugby field

Lyrics with a sentimental message

Haka. The word resonates in the throat like an axe on a tree trunk. As soon as it is uttered, a flurry of pictures go through our western minds. The first is that of fifteen men standing opposite their rivals on a rugby pitch, dressed in black shouting and hitting their huge chests and thighs. These men are the All Blacks, and have been selected to play on the New Zealand 15-man rugby team. They have been performing this dance before each encounter for more than two centuries. Not content with becoming the main propagation channel, they have made it an icon of Māori culture in the world. And yet we know practically nothing about it... What a terrible paradox. If was as if the sharing of this part of Maori cultural had been so sudden that there was not enough time for it to be understood by the West...

A haka is a ceremonial dance that has always existed in New Zealand, since the first contact with the Māori to the present day. In the Māori language, “haka” means “dance”. A haka is an original creation, just as a song or choreography is. There are therefore an infinite number of them. And, if, on the whole, westerners only remember the physical and visual dimensions, the language barrier prevents them from appreciating its most fundamental aspect: its message.

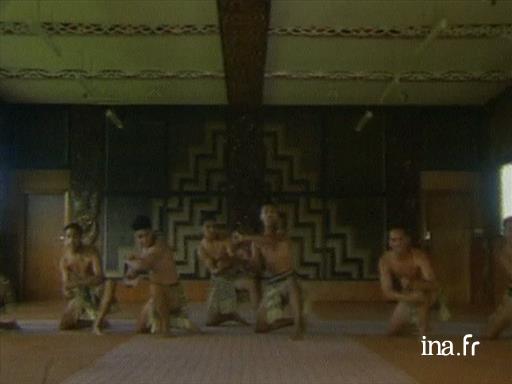

One mustn’t forget that in pre-colonial times, Māori culture had no form of writing. As a result, the process of knowledge transferral was done orally, and traditional dances were part of this process. A haka can be about a founding myth, the history of a tribe, or an event in history. But it is also a creation that is in keeping with its times, and can deal with any subject of modern society, be it positive or negative.

Tradition of the haka

During our ethnographic study carried out in the Waikato region in 2008, students were asked to write a haka warning their peers about the ravages of alcohol among students, a little unusual, you might think. It is true that we are far from the redundant stereotype that reduces the haka to a mere war dance... There are a few main types of hakas. Some are ceremonial orders (haka taparahi), others are war cries (haka peruperu) or some are even funeral dirges (haka maemae). But all are rooted in the same founding myth, that of Tane-Rore.

From Tane-Rore to "concert parties": a journey back through time

In Māori mythology, the dance came from Tane-rore, son of the Sun God Tama-nui-te-Ra and the Women Ete Hine-raumati. Tane-rore was the fruit of the union between the Sun and heat; he represents movement. The Māori say it is possible to see him dancing during air tremors when it is very hot, or when sunlight flickers on waves. Today, Tane-rore is alseo embodied in the tremor that shakes the hands of dancers, called the wiri wiri.

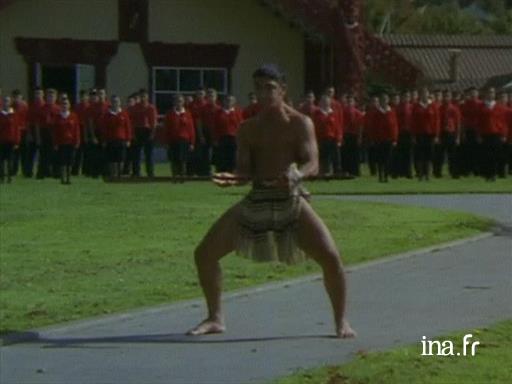

The first stories that mention the haka were told by the navigator Abel Tasman, who, on 18th December 1642, became the first westerner to come into contact with the Māori in Taitapu on the northern tip of South Island. It was an encounter that unfortunately ended in tragedy because after two days of distant exchange full of misunderstanding, a clash between the two sides occurred, causing the death of the three Dutch sailors. Tasman ordered his two boats to pull up anchor immediately, and christened the place the “Bay of the Assassins". It took 127 years before a European was to return to New Zealand. On 8 October 1769, Lieutenant James Cook landed near Gisborne, on the east coast of North Island. Once again, the westerners were frightened of the local tribespeople, and killed a Māori for no apparent reason. Gradually, the two peoples came to know each other better, and some settlers, albeit rather fearful, became interested in the art of the haka. Others, such as Christian missionaries violently condemned these dances that they deemed savage. The practice nevertheless continued. And it evolved, and so did Māori culture and its traditional dances, which were gradually categorized under a set of performative Māori arts now called "kapa haka” (“group dance'). The haka is one its five disciplines.

The first driving force behind this development was tourism, which the English wanted to promote in a country that they wanted to be "the final jewel in the English Crown". From the mid-19th century, the region of Rotorua and its magnificent natural sites shaped by geothermal activity became a mecca for tourists. Very quickly, concert parties, and dance companies were created in order to meet a growing demand. Of course, these shows were not intended to represent traditional Māori music - which westerners found monotonous and unbearable - but rather to keep them satisfied as they wanted to see a little Māori culture during their stay. The so-called "concert parties" therefore used western melodies, the sounds of jazz and blues, as well as the guitar, which soon became an important instrument in Māori music. These shows offered a selection of the performing arts, which included poi dances (the harmonious and synchronous swaying of white balls attached to a cord) and the haka.

Queen Elizabeth visits the Māori

As part of her official trip to the different Commonwealth States, Queen Elizabeth II visited New Zealand on 6th to 18th February. On 6th February in Waitangi on North Island, the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh greeted the Island's officials before attending a Maori ceremony including a haka performed by warriors.

This is the culture the tourists expected to see: the poi dances and the haka matched their ethnocentric representations of beautiful native girls and fierce Māori. This is how Māori performing arts began to be separated according to gender: the haka became masculine, and the *poi * feminine. This was absurd really, when we know that women originally played a leading role in the haka: not only by providing powerful vocal support to men from the back or on the sides, but also by ensuring the magical protection of the group by virtue of their sexual organs, which were considered sacred in pre-colonial times. The same can be said about the poi, which, historically, was never exclusively reserved for women, since it was an exercise imposed on young boys to help develop their skills and strengthen their forearm muscles so as to better handle weapons.

The first competitions

The concert parties, which were promoted by the tourist industry, continued to organize tours. The idea of staging competitions for traditional dances was suggested a few decades later, in 1934, by Lady Bledisloe, the wife of Charles Bathursht, Viscount Bledisloe, while she was making a royal visit. This was a real novelty, because even if emulation and competition were associated with tribal identity in colonial times (remember that the Māori were never a united people, but rather a myriad of tribes that maintained friendly or hostile relationships with each other), there was no formal or coded way of identifying the winner, and even fewer trophies to hand out. But Lady Bledisloe insisted, and so the first prize was awarded to a group of dancers from Rotorua.

Today, the "kapa haka" has all the features of a real sport, with its own rules, its own institutions, its own practice sites (schools, colleges, army, Māori communities), its own competitions and its own elites. In its current form, a kapa haka performance lasts thirty minutes and involves forty men and women spread out equally. It includes five disciplines: a choreographed start (whakaeke), a secular prayer (*moteatea *), an action song * (waiata-a-ringa), a poi dance (synchronous choreography using small white balls on a rope), a haka, and an exit (*whakawatea *). Each discipline is awarded a mark out of a hundred by a dozen judges, and it is not uncommon that the winner or loser is decided by a tenth of a point. The largest competition, known as the Te Matatini, is held every two years in New Zealand and is broadcast by the national channel. In the meantime, groups compete in regional competitions in order to qualify. Clearly, the haka, as well as the other Māori performing arts, have now become high-level performance sports. During our ethnographic study in 2008, several of those interviewed liked to say that winning the Te Matatini was as difficult as being selected for the All Blacks. And they were not far from the truth, if you think about the colossal work involved in creating, writing, learning and rehearsing a 30-minute performance with forty dancers. Finally, it is interesting to note that, in the past few years, *kapa haka * groups have formed in Australia and even in London, where there are large Māori communities. For the “Ngati Ranana” (the groups based in London"), these competitions were a means of promoting their culture abroad, as well as allowing them to feel less homesick.

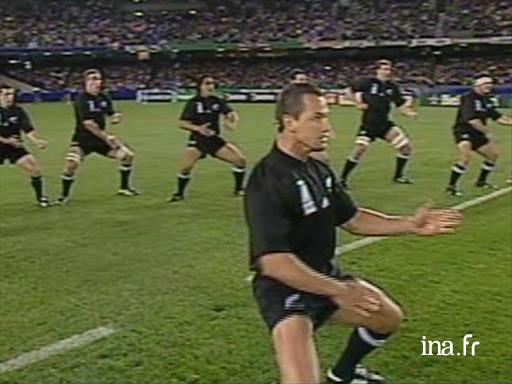

The Black ambassadors

But however commendable the efforts of the London Māori community may be, the most powerful emissaries of the haka, without a doubt, continue to be the All Blacks, the New Zealand 15-man rugby team, who have been performing this dance since 3rd October 1888, on the occasion of its first international tour. That day, the New Zealand team known as the "Natives" (as a large part of the team were Māori) played against Surrey, and performed a haka, the lyrics of which were “Ake ake Kia kaha”, meaning “let us be strong, again and again”. New-Zealanders began to perform the “Ka mate" from 1905 onwards, when there was a new tour to the United Kingdom.

However it is important to stress the irregularity of this practice, because in actual fact they didn’t perform it a single time during the England tour in 1935-36, while ten years earlier, a haka had been especially written for the 1924 tour. Also note that it was almost never performed on New Zealand soil when the team played at home.

It wasn’t until 1987 that the "Ka mate" was systematically performed before the start of every All Black match, at the request of Captain Wayne "Buck" Shelford and the team’s hooker Hikatarewa Reid. Both from Rotorua, they were sensitive to the importance and the meaning of the haka in Māori society and insisted that their partners perform it with rigor and intensity, something that had not always been true in the past. Shelford and Reid re-explained the words, taught the pronunciation and the moves, before organizing collective rehearsals until the group was perfectly in sync. The change was radical, and tribal leaders were delighted to see that the All Blacks were living up to their cultural heritage in the very same year that the first rugby World Cup was held on New Zealand soil. The All Blacks were quickly copied by the other nations of the Pacific.

On 27th August, 2005, the All Blacks caused a sensation by performing a new haka against South Africa in Dunedin.

Named the "Kapa o Pango”, it sparked a veritable tornado of questions: had it replaced the "Ka mate?" Why had it been written? What did it mean? In reality, it had not replaced the "*Ka mate *", but complemented it. Its author, the influential leader Māori Derek Lardelli gave the following explanation: “the hakas are like a family, "Ka mate” is a big brother, "*Kapa o Pango *” is the little brother. You cannot replace one family member with another. And this is how Māori think: in their culture, dances are not only forms made by the body, they are fully fledged persons. We understand better now why they have travelled so easily across space and time... without needing a visa, of course.