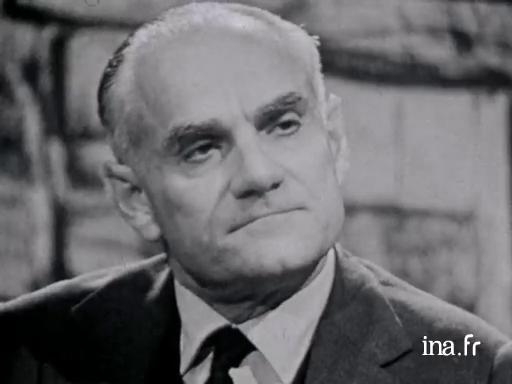

Alberto Moravia on the subject of L'Ennui

Information

Conversation with Alberto Moravia regarding his latest novel L'Ennui. The author discusses the subject of his book, the impossibility of owning a human being and the incommunicability between two people.

Context

The childhood of Alberto Pincherle (1907-1990), known as Alberto Moravia (borrowed from his paternal grandmother's name), is marked by tuberculosis of the bones and eight years of sanatorium, which he takes advantage of to discover literature and to write Time of Indifference (1929), which critics considered to be one of Europe's first existentialist novels, and which brought him success, but also hostility from the fascist regime.

At first, he preferred to get away from Italy for a while to travel with his first wife, writer Elsa Morante. He came back after having published Le Ambizioni Sbagliate (1935), a censored work that led to him being considered as subversive by the authorities, and he hid in the Romanian countryside where his novels take a more social turn, while his political conscience forms and his relationship with the Communist Party intensifies, since he became their European deputy (Agostino, 1944).

After the war and his blacklisting by the church in 1952, Moravia's work became more psychological, and he revelled in dissecting the morals of Romania's upper class society (The Roman Stories, 1954), love between couples (Conjugal Love and Other Stories (1954), made into a film by Godard) and also the frustration of modern day man in an industrial society governed by money and materialism (Boredom, 1960).