Brassaï and Paris

Information

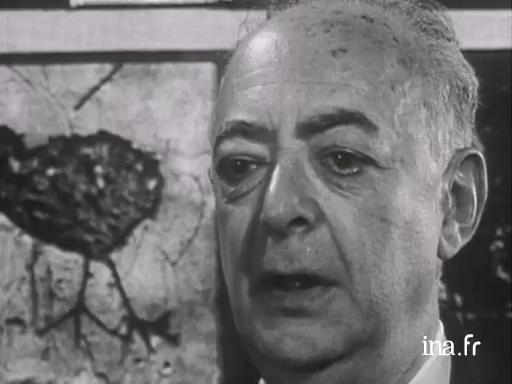

Interview with Brassaï on the subject of his pictures of night and graffitis. He tells an anecdote about a graffiti that Picasso made on a Parisian wall; someone cut out the wall to recover this "work". He talks about his way of photographing portraits, by asking those who are posing for him to look at him with an intent look.

Context

Born in 1899 in Brasso, in what is today Romania, Gyula Halasz or Brassaï, made his first trip to Paris in 1903 - 1904 with his father, Professor of French literature.

Back home, he studied painting and sculpture at the Academy of Fine Art in Budapest. He moved to Berlin in 1921, where he met Kandinsky and Varèse. But it was in 1924 that he made his dream come true: to live in Paris. There, he frequented the circle of poets and writers (Michaux, Queneau, Desnos, Prévert...), he began journalism and photography and took on the name Brassaï, after his birth town.

From 1930, he began photographing gardens, streets and walls in Paris with their misery, graffiti and their nocturnal images. But he also made photographs of high society and portraits of his artist and writer friends.

Brassaï's talents are plenty: painter, drawer and sculptor, photographer and filmmaker (Tant qu'il y aura des bêtes, 1954) and writer: he published numerous books and articles. Considered as one of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century, he died on the 8th of July 1984.